Saturday morning, May 26, 2012, a convoy of ‘Centrotrans’ buses leaves Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia and Hercegovina, heading eastwards into Republika Srpska to Višegrad, a town straddling the Drina, a beautiful river whose green waters cleave northward through the deep, wooded valleys of eastern Bosnia. The buses are headed to the 20th anniversary commemoration of the town’s ethnic cleansing. During 1992, Bosnian Serb nationalists, locals who were aided by Serbia proper in the form of the Yugoslav National Army, ‘cleansed’ the town and the surrounding hamlets of their Muslim neighbours. Their remains can now (not) be found at the bottom of the green Drina or in mass graves around the locale.

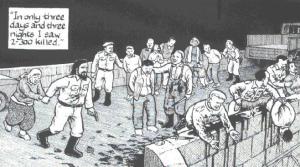

The people filling the buses this grey morning are relatives, refugees and victims, all going back to commemorate or to bury family and friends. What took place in Višegrad has yet to be officially labelled as genocide. The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) trials have failed to designate the crimes with that status, yet it is difficult to see it any other way. Some 3,000 Bosnian Muslims were identified, seized and then slaughtered by a mixture of local police and the Army of Republika Srpska. On June 14th, 1992 in a house on Pionirska Street, Višegrad, fifty-nine Bosniak women and children, along with the elderly, were burnt alive. Milan and Sredoje Lukic, cousins and leaders of the local Serb nationalist militia, then repeated the crime thirteen days later in Bikavac where sixty Bosniak civilians were locked into a house and then burned alive.

Up in Vilina Vlas, a spa close to the town, a rape camp was established; some reports claim that as many as 200 women were held there. It is now a spa once again. You can buy postcards of it in the tourist shop just off the Mehmed Paša Sokolović Bridge. This bridge–the beautiful, famous bridge built in 1571 by the Ottoman empire, immortalised and seemingly immortal–is at the heart of a Nobel prize-winning book,The Bridge on the Drina, penned by long time Višegrad resident, Ivo Andric. The bridge was the centre-piece of Višegrad’s beauty, standing unmoved by time and tide with a deft, yet solid elegance as empires rose and fell around it. Rumour has it, though, that some among the town’s older generations no longer walk on it. Perhaps they remember when it was awash with blood as their Muslims neighbours were brought to be killed on it, their throats slit before they were pushed into the writhing river below.

This event is both a commemoration and a burial. Sixty six people are to be buried, their remains gathered from Lake Perucac, a man-made lake downriver towards Srebrenica. The remains of other victims are gathered from other sites. All DNA identified, they are to be laid to rest in the Muslim Straziste cemetery which stands just off Ulica Uzitskog Korpusa street, named after the Uzice Corps, the Serb-led corps of the Yugoslav National Army that took the town in 1992. Next to the cemetery hangs the ubiquitous flag of Republika Srpska. Višegrad is now a Bosnian Serb town. The cemetery is the only land left to the people who have either lived or died there as Muslims. There are two token mosques, but neither is used.

The Centrotrans buses, having crossed the beautiful, waterlogged heights of Romanija, bring several thousand people back to a place they once considered home. It had rained during the night and the ground is damp; the freshly dug graves have water at the bottom. The prior week, a team of volunteers had come out and cleaned the cemetery, cutting the grass and branches and clearing the place for today. As the ceremony begins, a monument, an enlarged replica of Nisan, the headstone erected above Muslim graves, is unveiled, inscribed with text on all four sides. It stands under a newly erected flagpole from whence the Bosnian flag now hangs. The monument is unveiled by two girls who had come to bury their grandfather. They are being filmed by Al Jazeera Balkans as the Bosnian national anthem is heard throughout the town. The ceremony is long. For non-Bosnians and non-Muslims, it is difficult to follow. Even more difficult is interpreting the mood of the people. Similar to many other such ceremonies across Bosnia, imams stand, chew gum and chat as prayers are called and people are buried. The weeping of widows, sisters and mothers is mixed with general conversation. People answer cell phones with a loud, jocular “Hej, gdje si? Sta ima?” In In previous years people would sit and watch, eating sandwiches, although this custom is now banned. The ceremony culminates with the burials of sixty-six Muslims in the now familiar timber coffins with a green cloth-covered frame, numbers and a name displayed on the front. Sixty-six people, twenty years later.

After this everyone descends through the silent town. Children leaving school stand and stare. They do not remember a Višegrad with a Muslim population; they do not remember a war. They know only what they are taught by their parents and in school. The rest watch impassively from windows and balconies. Everyone is hyper-sensitive to any signs of trouble or provocation. There are none. The younger adults of the town do not hide their smirks, however. We pass “Andricgrad,” a new mini- town being built by movie director Emir Kusturica and funded in part by Milorad Dodik, President of Republika Sprska, personally. It will be the set for a film production of Bridge on the Drina. One imagines that in the now homogeneously Serb town of Višegrad the director may well have to reinterpret Andric’s depiction of the town (and its bridge) to reflect the new Muslim-less history that is now commonplace in Republika Srpska. The crowds gather on the bridge, filling it. The sides are lined with roses, and from the parapet of the bridge two long strips of red cloth dangle. Then, more speeches. The cafe adjoining the bridge makes a great place from which to view the proceedings; it is filled with both residents and people who have come for the ceremony. Some of the locals leave; others sit back and watch. Two lads in particular grin and raise their glasses to each other. The cafe owner turns the music up to drown out the speeches; the bouncy euro-techno beat of “Du hast den schonsten arsch der welt ” [“You have the most beautiful arse in the world”] drifts out across the river. On the bridge the speeches continue for another half an hour before finally the roses are cast into the water to the sound of Michael Jackson’s “Beat It” seeping out from the cafe.

The Centrotrans buses are now lined up and waiting, and the bridge empties quickly. It is a two and a half hour trip back to Sarajevo. Turning back to look as the buses pull away, the bridge stands immortally, hopefully a silent, terrible witness, a monument unintended. And beneath it the green Drina continues to flow. I doubt Višegrad will ever be beautiful again.