CHAPTER ONE

Blood and Vengeance

One Family’s Story of the War in Bosnia

By CHUCK SUDETIC

W. W. Norton & Company

HUSO CELIK entered the world, grew to manhood, and raised his family in eastern Bosnia, on the upper reaches of Mount Zvijezda, or Star Mountain. This mountain is a bulwark of earth and limestone, and its crest has marked out one stretch of Bosnia’s border with Serbia for much of the last six hundred years.

Signs of this border’s troubled past abound on Mount Zvijezda. Amid its meadows are the stone ruins of an army barracks and the crumbling trenches where border guards once fought and died. There is a vacant, weather-beaten building that was once a customhouse, and far below it lies an empty meadow known by all the locals as the Customs Area. There are ancient gravestones decorated with daggers and swords and inscribed in languages no longer spoken on the mountain. Etched into its living rock are crude stick-figure eagles with proud, outstretched wings; mystical swastikas; and horse soldiers with helmets and drawn swords. The peasants call these pictographs “the Roman Signs” and believe they are almost as old as the mountain itself Someday, the peasants say, someone will come and decipher the secret meaning of the Roman Signs. Then a massive river will gush forth from the rock and devastate the land for miles around.

Parents and grandparents have prepared generations of Mount ZviJezda’s children for the uncertainty of life on the border by telling them stories of the soldiers and the bandits and the greedy landlords who have ravaged the place over the years. They have told and retold their memories of fathers and mothers, uncles and aunts, and grandfathers and grandmothers who died by violence and whose deaths were never avenged. They have discreetly pointed out killers still living within shouting distance, still working their fields and tending their flocks, still smiling as they stroll by the house on their way home. These tales have taught generations of the border’s children that a smile may always be something other than a smile. They have ingrained in them the assumption that Mount Zvijezda might well have never seen a generation come and go in peace since its creation.

EVEN the children of Mount Zvijezda can tell snippets of the story of Jerina the Damned, the legendary villainess who created the mountain. Jerina was foreign born, the wife of a hated despot who once ruled the countryside for miles around. She henpecked her husband and built the mountain as part of a fortress to defend her husband’s territory against invaders and brigands. Jerina, the legend goes, used black magic to fashion from water alone an entire legion of giant soldier-slaves. Each morning, rain or shine, she ordered these slaves to line up in long human chains and pass boulders from one to the next. Month after month, Jerina’s slaves toiled. Year after year, they piled up the boulders and secured them with stones and dirt until they had formed a wall rising some three thousand feet above the valley floor and extending for twelve miles more or less from south to north. Every few miles along the top of the wall, Jerina’s slaves built up rounded peaks that jut skyward like watchtowers. Between these towers, the slaves left passes accessible only by steep footpaths that rise like stone stairways, On the sides of the mountain, the slaves also cut fissures and tight passages into the white rock. These open into an underworld of eaves and grottoes, ice-cold subterranean rivers, and vertical shafts that plunge into pitch-black pits that seem to have no bottom.

Jerina had the western wall of Mount Zvijezda buttressed with terraces of earth anchored by outcroppings of rock. These terraces are cut by creeks that turn into angry torrents after each snow melt and rainstorm. Covering the terraces are forests of beech, oak, and pine as well as rolling pasturelands, meadows, and rows of pear, apple, and plum trees that mark off vegetable patches and small fields of potatoes, wheat, and spindly corn. Unpredictable gusts of wind blow down from the top of the mountain wall and up from the valley floor. The air carries the aroma of manure, pine resin, and wood fires along with the gurgle of falling water, the screech of birds of prey, the tinkle of cowbells, and the “Yeoooo! Yeoooo” of peasant men and women summoning one another as they tend their flocks or work their fields.

Life on Jerina the Damned’s mountain has made these peasants cautious even in their singsong calls to one another. I once heard Huso Celik’s lifelong friend, a Serb named Dragoljub Radovanovic, yodel to his wife, Zora, one spring afternoon. The Bosnian war had ended by then, or seemed to have ended. Zora and her sister were down in a meadow below their cinderblock house. They were using a pair of paper scissors to shear their sheep and were stuffing the fleece into plastic bags. “Yeoooo! Yeoooo!” Dragoljub called down to them. “Come on hoommme! Someone’s commme to visit. Commme seeee! Someone’s commme to visit.”

I had brought someone with me–Harried’s mother, Hiba. The glaucoma had fogged up Dragoljub’s eyesight so badly by then that he had had to put on his glasses even to try make out who it was climbing the path toward his house. It took him a few seconds more to recognize Hiba. He had known her for years, but she had disguised herself. She had not covered her squirrel-colored hair with a kerchief, and she was wearing a skirt instead of dimije, the billowy bloomers tied at the ankle that Muslim women on the mountain had always worn. Dragoljub was discreet. He did not shout out the visitor’s name when he called to Zora. The other Serbs in the village would have heard him. No good would have come of it. “We’rrre commmmmin’,” I heard Zora yodel from the meadow below. “We’rrre almmmmooossst dooonnne.” She never yelled up to ask who had come to visit.

AT the foot of Mount Zvijezda’s western slopes, far beyond yodeling range from Dragoljub’s house, the turquoise waters of the Drina River flow northward, parallel to the mountain for its entire length. Jerina the Damned had to keep the river from flooding her land. So she channeled the Drina out through the walls of her fortress by cutting a forbidding gorge that separates Mount Zvijezda from Zlovrh, or Evil Mountain, its twin to the north. The gorge begins at a riverside village known as Slap, right where the Drina makes an unnaturally sharp eastward turn. A few miles farther downstream, Mount Zvijezda drops the burden of the Bosnian-Serbian border onto the Drina’s back, and the current carries the border for the rest of the river’s journey northward.

At about the time of the birth of Christ, legions of foreign soldiers conquered Bosnia and merged it into the vast blend of tribes, peoples, city-states, and colonies called the Roman Empire. The Romans built villas and roads in the Drina valley over the next four hundred years. Latin became the language of the land. Caravans traveling northward from the Adriatic seacoast loaded their cargo onto rafts and steered them downstream or followed a minor trade route beneath Mount Zvijezda and along the Drina’s right bank. Ferrymen transported some of these ancient travelers and their pack animals across the river near Slap. After reaching the left bank, the caravans entered a narrow valley now known as Zepa. Then they zigzagged their way up the side of Zlovrh before descending through a forest into a mining town that had grown up around rich silver and lead deposits. The Romans called this mining town Domavium Their slaves, mostly prisoners of war and their offspring, dug the silver, smelted it, transported it down the Drina on barges, and minted coins from it.

The Drina’s long experience as a border began during Roman times, in A.D. 395, when the sons of Emperor Theodosius split the empire and used the river to mark the frontier between its Latin-dominated western half and its Greek-dominated eastern half. Within a few centuries, the Western Roman Empire collapsed into the chaos of the Dark Ages. Barbarian invaders from the East, including Croats, Serbs, and other Slavic tribesmen, wiped out Bosnia’s Latin-speaking Christians and plundered their towns, churches, and villas in the Drina valley. Bandits halted the caravan traffic. The Roman roads fell into disrepair. Domavium’s mines closed. And the Slavic tongue replaced Latin as the language of the land. Domavium’s name was recast using the word srebren, the Slavic adjective for silver, and the town came to be called Srebrenica.

No single empire held sway over southeastern Europe during the centuries after the conversion of the barbarian Slavs to Christianity and the Great Schism of A.D. 1054, when the Roman Catholic pope and the patriarch of the Eastern Orthodox Church tore the main body of Christianity in half and left Bosnia dangling in the middle. The Slavic princes and feudal landholders who ruled Bosnia in the Middle Ages prospered for a time by reopening Srebrenica’s silver mines. But they soon found themselves under pressure from the east by the Orthodox princes and despots of medieval Serbia and from the north and west by the Roman Catholic kings of Hungary and the feudal leaders of Hungary’s vassal state, Croatia. The names of many of these rulers–King Sigismund, Djurdje Brankovic, Despot Stefan, and many others–have long since faded from the memory of most of the peasants on Mount Zvijezda. But the mountain folk perk up and smile when they hear the familiar name of Jerina the Damned, as if this foreign-born villainess who conjured up an army of giants from water to build Mount Zvijezda embodied all of the evil incarnate in all of the men who ever ruled over it, as if Jerina had come to represent the danger that would make an old Serb with glaucoma afraid to shout to his wife that a Muslim woman had come back to the village for a visit.

“Oh, that Jerina the Damned, that Jerina the Damned,” the toothless mouth of one of the Celiks’ great-uncles once sighed when I asked him about her. His nickname was Penzija, “The Pension,” and he was about ninety years old and almost cut off from the world by deafness. “She is damned, that Jerina,” he repeated.

“Why? Why is she damned?” I asked.

“Huh?”

“Why?” I shouted. “Why is she damned?”

“She is damned and has always been damned. The people damned her. And that’s all I can say about it.”

* * *

JERINA’S bulwarks failed to protect Bosnia from the last great incursion against Europe from the East, the invasions of Ottoman Turk armies into the southeastern corner of the continent beginning in the fourteenth century.

The Ottoman Turks evolved from an obscure band of nomads who fled the Mongol invasion of the Central Asian steppes in the early thirteenth century. They took refuge on a rocky plateau in central Anatolia and began, under a sultan named Osman, to expand their territory westward at the expense of their new Orthodox Christian neighbors. Within a few decades, the descendants of Osman had assembled a military juggernaut that fed itself on conquest, plunder, and tribute, and they laid the foundation for the second lasting empire, after Rome, to master the Balkan peninsula. The Ottoman Turks tore apart Orthodox Byzantium, the remnant of the Eastern Roman Empire that had been worn threadbare by centuries of internal strife and an invasion by Roman Catholic crusaders. On Vidovdan, the feast day of Saint Vitus, June 28, 1389, the Turks barely defeated a Serbian-led Christian army in a battle at Kosovo that would become the grist of the Serbian nation’s founding myth centuries later. After a setback at Belgrade in 1456, which has been marked throughout Christendom ever since by the tolling of church bells at noontime, the Ottoman armies overran the rest of Orthodox Serbia. Sultan Mehmed marched his armies across the Drina into Bosnia in 1463 and put its princes and feudal landholders to the sword. Ottoman seamen seized one seaport after another, harassed shipping on the Mediterranean Sea, and took control of the overland trade routes to China and India. This prompted the Catholic king and queen of Spain, the same Ferdinand and Isabella who had expelled the Muslim Moors from their last handhold in western Europe, to take a gamble on Christopher Columbus to find them a new trade route to the Far East. Three decades after the discovery of America, the Ottoman armies conquered Hungary and threatened to lift the star and crescent of Islam over even more of European Christendom. Only then, only when minarets were casting their shadows on the rolling plains before Vienna–and just a few hundred miles from Renaissance Venice and Florence–did Austria’s ruling family, the Habsburgs, summon the will to mold from a rabble of jealous princes and petty despots a Roman Catholic empire capable of warding off the prospect of imminent destruction.

Bosnia’s medieval princes had received scant support from the Roman Catholic world in defending their lands from the Ottoman forces. Most Bosnians were crude shepherds and peasants, tenant sharecroppers who had no idea of nationhood. They had never shown much obeisance unto the established Christian churches and paid even less heed to the Catholic and Orthodox warriors and merchants who invaded their land and sometimes sold their kinfolk into slavery. Many of eastern Bosnia’s landholders and peasants were members of a home-grown Bosnian Christian Church, a sect persecuted by the popes of Rome and the Serbian Orthodox bishops as heretical.

After the Ottoman invasion, Bosnia’s peasants became the sharecroppers of Muslim landlords, soldiers rewarded by the sultan with temporary custody of estates seized from Bosnia’s ousted feudal families. The dues the Christian sharecroppers owed their new masters actually decreased from what they had been paying before the conquest, and peace returned to the land for the first time after decades of turmoil. Over the centuries, many Bosnian Slavs accepted the religion of their foreign conquerors. The song of the muezzins called the new faithful to prayer each day from minarets. The young boys were circumcised each spring by traveling barbers. Consumption of pork was forbidden. And every woman covered her face with a veil from her sixteenth birthday to the end of her life. Conversion to Islam brought reduced taxes and the full benefits of citizenship in a vigorous, overarching power that seemed predestined to conquer the continent. Muslims willing to fight found opportunities to rise to positions of authority in the military and acquire wealth by pillage and plunder. But the vast majority of the converts were, and would continue to be, peasants and herdsmen who were as dirt poor, illiterate, and ignorant as their neighbors who chose to remain Roman Catholics or Orthodox Christians.

Although Islam was the official religion of the Ottoman state, the sultan exercised religious tolerance. He resettled in Bosnia’s towns many of the Jews expelled by Ferdinand and Isabella from Spain in 1492. The Greek patriarchs of the Eastern Orthodox Church found a new patron in the sultan, who gave them political and judicial jurisdiction over most of the Christians within the realm, an authority they had never enjoyed under the Christian emperors of Byzantium. The sultan exempted his Christian subjects from serving in his military but required them to pay higher taxes than the Muslims. For several centuries, the sultan periodically ordered Christian families to surrender to him male children, who were forced to accept Islam and remain imperial slaves for life. These boys were schooled in Turkish, Arabic, and other languages and given elaborate training in the military arts and statecraft. Some were inducted into the most elite unit of the imperial army, the Janissaries, while others were assigned to administer the sultan’s government. These slaves enjoyed privileges and so much potential for upward mobility that some Christian families volunteered their sons for the sultan’s “blood tax.” Since freeborn Muslims were barred from the government and the Janissaries, Muslim parents sometimes bribed the sultan’s tax collectors to take their boys or secretly left their sons uncircumcised and gave them to their Christian neighbors so that they could, in turn, hand the boys over in payment of the tax.

* * *

THE limestone mosque a minute’s walk away from the Celik family’s homestead on Mount Zvijezda is the largest mosque in the entire district. It stands at the intersection of two rocky trails, and all of the peasants living nearby call this place “the Cross.” The Serbs say the mosque was built atop the ruins of an Eastern Orthodox chapel, and they argue that the Cross would never have gotten its name if it had not been for the crucifix that once stood atop the chapel. The Muslims, however, insist that the mosque was built from the ground up by a certain Juz-bin-Kulaga, the commander of thousands of Ottoman soldiers, who was granted land on Mount Zvijezda by the sultan. Juz-bin, they say, was laid to rest next to the mosque under a gravestone whose top had been chiseled into the shape of a turban. No one remembers when or how Juz-bin died. No one even remembers whether he was still alive on a fateful summer day when the local hodza, the Muslim clergyman assigned to the mosque, climbed the spiral stairway inside the minaret, peered out over the fields and meadows from its circular porch, and called the faithful to the afternoon prayer.

“Allahu ekber! God is great!” the hodza sang. Then he noticed something unusual down below and paused for an instant. “Allahu ekbe … Yeoooo! Yeoooo! Therrre’s a cooow in the caaabbage paaatch! Yeoooo! Ycoooo! Get the cooow! Get the cooow!”

Elsewhere in the realm of the sublime sultan, perhaps, such sacrilege would have caused a scandal and a swift meting out of punishment. But the sides of Mount Zvijezda rumbled with laughter, and the Muslim and Orthodox peasants bestowed upon the hamlet next to Juz-bin’s mosque a new name that has made people cluck about that cow in the cabbage patch ever since. Kupusovici, they called the place. KOO-poos-oh-vee-chee, Hamlet of the Cabbage People.

ITINERANT dervish mystics and the hodzas who served at Juz-bin’s and other nearby mosques provided the only education on Mount Zvijezda, and its Orthodox Christians went without schooling entirely. A handful of the Muslim men learned to read the Arabic of Islam’s sacred book, the Koran, and to write their Slavic language in the Arabic script; a rare one among them would master the Persian of the Sufi mystics and poets. The hodzas and other self-taught Muslim holy men known popularly as mullahs prayed over the sick and worked cures by feeding them pieces of paper on which they had scrawled out passages from the Koran in Arabic letters with goose quills dipped into ink made from grass. Both the Muslims and the Orthodox Christians had women and men who conjured up potions and charms from leaves, rags, fingernails, and ashes and promised that these would ward off disease, break up a marriage, stop a kid from wetting the bed, or dry up the udders on the neighbor’s best cow. Old women and men would melt lead and drop it into pails of water, and from the shapes taken by the globs of cooled metal they would tell someone’s fortune, exorcise demons, and assuage fears. If a mullah or a hodza or a faith healer proved particularly adept, the sick, the barren, the jealous, and the vengeful would ignore their religious differences and seek their help.

The age-old agricultural cycle on Mount Zvijezda turned without interruption. The peasants raised and harvested their crops by means of wooden plows and other primitive implements. The women sheared their sheep, spun and dyed the wool, and wove it into cloth. The proper time for plowing, planting, and harvesting was set according to the saints’ days on the Orthodox calendar and, since no one really remembered anyone’s birthday, children were told that they came into this world “during the plowing,” “with the beans,” “with the plums,” or, for an unfortunate few, “with the manure.” Bosnia’s feudal landholders, who were known as beys, kapetani, and agas, recruited thousands of Eastern Orthodox peasants from Montenegro and other regions beyond Bosnia’s borders to work their fields as tenant sharecroppers. The landrich and money-poor Muslim landlords on Mount Zvijezda, including the Suceska beys of Odzak, the hamlet a few hundred yards west of Kupusovici, brought in whole families of Montenegrin tribesmen, a rough-and-tumble highland people who were so poor that they distilled their brandy from grass. They also practiced the most ancient of all methods of maintaining social order: blood vengeance, a custom that requires the men of one family to kill any male member of a second family if someone from the second family has caused the death, even by accident, of someone from the first. It was literally a head for a head, and the retaliation could be carried out at any time and by any means, including a knife to the back. Blood vengeance was a matter of customary law when there was no other law. It was a matter of family honor from which only women and pre-teenage boys were exempted.

The ancestors of today’s Radovanovic family came to Mount Zvijezda with these Montenegrins, The Lukic family came to Rujista from a Montenegrin village called Lipovac, and its members worked as sharecroppers for an aga named Zahic. The Celiks themselves might have come from Montenegro during the same period. After the Orthodox Montenegrins’ arrival, Muslims continued to make up the majority population on Mount Zvijezda; but in Bosnia as a whole, the Orthodox soon outnumbered the Muslims and Catholics.

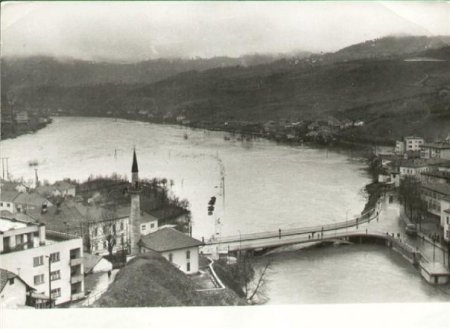

VISEGRAD, the town nearest to Mount Zvijezda, grew up on the right bank of the Drina at the site of a medieval ferry landing about ten miles south of Kupusovici. In the sixteenth century, Mehmed Pasha Sokolovic, the most illustrious son of the Drina valley, transformed Visegrad into a bustling caravan stopover by spanning the river with a bridge. It is a miraculous bridge, with eleven white stone arches and a marble tablet calling upon Allah to bless it. At its center is a square balcony known as the sofa, and there, on the sofa’s stone benches, the townsmen of Visegrad gathered in the evenings to discuss the issues of the day. They gazed down into the swirling current of the river as they sipped frothy coffees said to be as sweet as sin, as hot as hell, and as black as a woman’s heart.

Mehmed Pasha was born to a prominent Orthodox family from a village upriver from Visegrad. He was handed over to the sultan in payment of the blood tax and rose by his wits, ambition, and luck to become the most powerful minister to perhaps the greatest of all Ottoman sultans, Suleiman the Magnificent. Mehmed Pasha never forgot his home or his Orthodox roots. He used his power to free the Serbian Orthodox Church from Greek domination in 1557. He had his brother appointed patriarch of the restored Serbian Church, allowed it to establish a new patriarchate in Kosovo, and gave it jurisdiction over all Orthodox Christians in Serbia, Bosnia, and other regions of the Balkans. As a result, many Eastern Orthodox peasants and herdsmen in Bosnia came to identify themselves in later centuries as Serbs; and Mehmed Pasha, a convert to Islam who commanded the sultan’s army against Christendom, is today regarded by the Serbs as a national hero. Ironically, Mehmed Pasha died from a knife thrust into his heart by another Orthodox convert to Islam, a dervish from eastern Bosnia seeking vengeance for the death of his spiritual master, who had been executed by the Ottoman authorities as a heretic.

Mehmed Pasha’s assassination left the Ottoman Empire in the hands of weak-willed rulers and marked the beginning of centuries of decline. Freeborn Muslims, who were less obedient to the sultan than his Christian-born slaves, gradually found their way into the Janissaries and the government administration. The estates granted temporarily to Ottoman soldiers were gradually transformed into hereditary feudal lands, and the landowners now had less reason to fear the whims of the sultan in far-off Istanbul. The Christian tenant sharecroppers who worked these feudal lands were now effectively stripped of the protection the sultan’s absolute authority had once provided. And it would not be long before the landowners began demanding that the sharecroppers pay extortionate dues.

* * *

THE last, desperate lunge by the Ottoman Empire against Christian Europe failed in 1683. Austrian, German, and Polish knights routed a huge Ottoman army besieging Vienna and sent the sultan’s forces retreating like a fugitive rabble eastward through Hungary. In 1686, the Austrians and their Catholic allies pried the Ottomans from Hungary’s capital, Budapest, and commenced, to Europe’s delight, the destruction of the Ottoman legacy on European soil. Budapest’s mosques and bathhouses were burned and razed. Muslim families, including the families of army officers who had once been the Ottoman feudal elite in Hungary, retreated into eastern Bosnia and other Ottoman territories and were desperate to reestablish themselves oil new land. The Austrians had practically reached the gates of Belgrade by the end of the century, when they paused to conclude a peace treaty. It was then that Russia, the Eastern Orthodox realm of czars who claimed the inheritance of the defunct Eastern Roman Empire, took up its sword and set about carving away new chunks of Ottoman territory. Soon the czar was demanding that the sultan grant Russia a protectorate over the Serbs and the other Orthodox Christians within the Ottoman Empire. Within a few decades, Catholic Austria and Orthodox Russia had begun competing to acquire Ottoman territories in the Balkans.

As the years passed, the sultan lost internal control of his empire. Rampant bribery and other forms of corruption sucked away his state’s vitality. Without the incentive of new conquests and plunder, the Ottoman military machine broke down. Local warlords became the de facto sovereigns of huge tracts of imperial territory. Lawlessness consumed the land as these warlords fought among themselves and against troops sent in by the sultan to restore imperial control. Common men resorted to blood vengeance to settle their scores. The conservative Muslim Slav beys, kapetani, and agas in Bosnia were desperate to cling to their land and privileges. They stymied attempts by the Sultan to reform his government and armed forces, just as the European powers had been modernizing their governments and armies in the wake of scientific advances brought on by the Enlightenment. This eighteenth-century movement in Western Europe stressed individual liberty, secularism, reason, and a spirit of skepticism. It gave birth to the ideals incorporated into the American Constitution and the Bill of Rights.

The Enlightenment also spawned a new state of mind that swept over all of Europe and later became the world’s dominant political attitude. This was nationalism. Under its spell individual Frenchmen, Germans, Hungarians, Italians, Serbs, and, somewhat later, Croats, began to sense that they owed their primary loyalty not to emperors, kings, or popes but to their respective nations. Soon this new sense of national loyalty developed into a hunger for the formation of “nation-states” independent of Europe’s overarching empires. In time, the idea of national unity overwhelmed the Enlightenment ideal of individual liberty, and from there it was a short step to the barbarism of modern warfare, to war waged not by a small class of feudal warriors or mercenaries but by an entire nation. During the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars, for the first time, men were mobilized en masse, willingly, or unwillingly to fight for the glory of France. In time, the other European nations mobilized national armies, and their aim became the creation of nation-states and, too often, the Subjugation or extirpation of entire foreign or minority populations within them. Men who refused to participate were castigated as traitors.

With support from Orthodox Russia, the Serbian Orthodox Church had become by the late 1700s the backbone of the emerging Serb nation. The Church had also become more of a nationalist than a religious organization. Serb priests mythologized the defeat at the Battle of Kosovo and demanded that it be avenged. They lauded the centuries-long resistance to the Turks mounted by the Orthodox clansmen in Montenegro and brigands in Serbia, who fought the authorities one day and collaborated with them the next. Priests in Montenegro began preaching a crusade not only to rid Serbia of the Ottoman Turks but to destroy the entire legacy of the Ottoman Empire, just as the Catholic Europeans had done, and to expel, or exterminate the Slavs who had converted to Islam.

The Serbs first threw off Ottoman domination in 1804. Russian-backed insurgents led by Karadjordje, or Black George, a prosperous pig farmer with Montenegrin roots, took control of a swath of land in central Serbia that reached to the passes atop Mount Zvijezda. The uprising held out for nine years before the Turks sent Karadjordje fleeing. Ottoman troops, with Muslim Slavs among them, retaliated against the Serb rebels by plundering their villages, enslaving Serb women and children, torturing and executing captured Serb leaders, and, in some places, murdering all males older than fourteen. These atrocities provoked a second Serb uprising, in 1815, which was led by an illiterate peasant named Milos Obrenovic. Obrenovic struck a deal with the sultan. The Serb delivered the Ottoman leader the severed head of Karadjordje and vowed to pay the sultan tribute if he would grant the Serbs autonomy in a patch of territory south of Belgrade. The deal held.

After Russia handed the Ottoman army another defeat in 1829, Obrenovic, with diplomatic support from Saint Petersburg, arranged for the expulsion of Muslim landowners and peasants from the region where the Serbs had won their autonomy. The Turks, however, were allowed to maintain garrisons in Belgrade and other Serbian towns. And Ottoman border guards now took up positions along the highest reaches of Mount Zvijezda to protect Visegrad and Mehmed Pasha’s bridge from Serb militias and prevent them from driving out the Celiks, the Suceskas, and the other Muslim families from Kupusovici, Odzak, and the other villages on the mountain’s western slopes.

Thirty years later, at about the same time that the U.S. cavalry was herding the native tribes of the American West onto reservations, Serbia’s ruling prince, Milos Obrenovic’s son, Mihailo, prepared a general Balkan uprising against the sultan. Under intense diplomatic pressure aimed at averting a regional conflagration, Turkey agreed to withdraw its military garrisons from Serbia’s towns. The Muslim townspeople were now expelled from Serbia, and their mosques were razed. These bitter Muslim Slav outcasts left Serbia for Turkey or found refuge on Mount Zvijezda and other areas of eastern Bosnia. By then, Serb nationalist leaders were laying claim to Bosnia and justifying their claim by arguing that medieval Serbia’s princes had controlled vast tracts of Bosnian land and that the Orthodox Christians, the largest segment of Bosnia’s population, were in fact Serbs. Soon nationalist Croat leaders staked their claim to Bosnia as well, arguing that the whole region had once been Roman Catholic, and therefore Croat. Both the Serbs and the Croats dismissed Bosnia’s Muslims as “ethnic Serbs” or “ethnic Croats” whose ancestors happened to have converted to the Muslim faith. The attitudes of the Muslim Slavs themselves were divided. Some Muslims considered themselves to be Serbs, others Bosnians, others Croats, and others “Turks” or simply loyal subjects of the sultan.

By the late nineteenth century, the force that had once unified the Austrian Empire’s disparate peoples, the danger of Ottoman expansion, had ceased to exist even as an illusion. The Hungarians, Czechs, Croats, Italians, Slovaks, Romanians, and other nations submerged within the Austrian Empire were clamoring for the creation of their own nation-states. Hungary’s status was elevated, and the Austrian Empire became Austria-Hungary. As Russia continued to expand its borders and influence at the expense of the Ottoman Empire, pressure mounted on Austria to do the same. Government officials in Vienna and officers in Austria’s army coveted Bosnia and other Ottoman lands. Their ambition to seize these lands put Austria on a collision course with the Serbs and their backers in Russia.

By 1875, the Ottoman Empire had gone bankrupt. Tax collectors in Bosnia resorted to violence in an attempt to seize grain from hungry sharecroppers after a crop failure. An armed uprising began with the tolling of church bells. Relations between the Serb and Muslim peasants ruptured in many areas, and the bloodshed dragged Bosnia onto the agenda of the international community for the first time. Serb peasants attacked feudal landowners all over Bosnia, and the landowners struck back by sending out Muslim irregulars who burned hundreds of Serb villages and killed several thousand peasants, Bosnian Serb nationalists proclaimed their loyalty to Serbia. They demanded an end to feudalism. They demanded ownership of the farmland they were working and sought Bosnia’s merger into Serbia. After a year of peasant bloodshed, Serbia and Montenegro went to war against the Ottoman Empire in a bid to seize its territory in Bosnia. Russian volunteers rushed to join the fight as if it were an Orthodox crusade, and the Russian government saved Serbia from defeat by intervening militarily and driving back the sultan’s troops to the very gates of Istanbul. Half a million Muslim Slavs, about a third of Bosnia’s population, now found themselves cut off from the receding borders of the Ottoman Empire; about six thousand of these Muslims were beys, kapetani, and agas who owned land tilled by about eighty-five thousand sharecroppers and their families, almost all of them Christian.

Europe’s ruling monarchies sought to prevent an explosion of sectarian violence in Bosnia and to maintain a balance of power between Orthodox Russia and Catholic Austria. At a peace conference in 1878, the European powers dashed Serbia’s ambition to inherit Bosnia and gave Austria the right to occupy the region for an undetermined period. It took Austria’s army only a few weeks to secure Bosnia’s borders and crush internal resistance to the occupation, which all but a few Muslims eventually came to accept as the will of Allah. The region’s Serbs initially reconciled themselves to Austrian rule but assumed that Austria’s Habsburg emperor, Franz Josef I, would abolish Bosnia’s Muslim-dominated feudal order and distribute the Muslim estates to the sharecroppers. The Serbs grew bitter, however, when no land reform was forthcoming. Their ambition to link Bosnia with Serbia had dismayed the Austrian emperor. He turned to Bosnia’s Muslim elite to garner support for the occupation and allowed them to maintain control of their feudal lands. Thus, Catholic Austria preserved the Ottoman Empire’s Islamic legacy in Bosnia instead of destroying it, as its Catholic armies had done in Hungary and as the Serbs had done in Serbia.

* * *

THE Austrian army stationed guards to keep watch over the border along the top of Mount Zvijezda. In Odzak, the guards built a stone customhouse next to the Radovanovic family’s homestead and took up residence in an old Ottoman barracks just below the house of a Serb family named Mitrasinovic. Each day the guards would climb the steep footpaths to the crest of the mountain wall and check travelers coming across from Serbia. They kept watch for horse and cattle smugglers and searched for men who were dodging the unpopular Austrian military draft. The border guards also registered all the stills on the mountain, and enforced limits on the amount of brandy the peasants were allowed to make.

It was probably sometime in the late 1880s when a lone Muslim who called himself Mullah Saban, and nothing more, crossed the border from Serbia into Bosnia. He soon made his way to Kupusovici and announced that he had bought the place along with most of Zlijeb, a village just within shouting distance to the cast. The Celiks and other sharecroppers in Kupusovici now became Mullah Saban’s tenants. They watched in wonder as he constructed himself a fine house so close to Juz-bin’s mosque that the shadow of the minaret fell on it on sunny mornings. He opened a store in a room on the ground floor of the house and sold coffee, sugar, and other staples to his sharecroppers.

Mullah Saban seemed never to have had a family of his own. But he got along well with the Celik menfolk and soon adopted their surname despite the fact that they were his tenants. Mullah Saban Celik, he now called himself, Mullah Saban “Steel.” He trusted the Celik men enough to give them a peek at some gold ducats he kept hidden away. They assumed Saban had stolen the gold. They figured he had kept his real surname a secret because he was on the run from some blood-vengeance vendetta across the border and did not want word of his whereabouts to get back to wherever it was he had come from,

Mullah Saban wanted desperately to have a son. Every Bosnian man in those days wanted to have a son. Sons were the only fitting heirs for a man’s material riches. Sooner or later a man’s daughters would run off and marry out of the family. Without a son, everything Mullah Saban had acquired would be cast to the capricious winds that blew down the mountain. He soon took a wife, a girl named Pemba, and brought her to his house next to the mosque. A year or so went by, but Pemba bore him no children. So Mullah Saban took a second wife, named Cima, but she too seemed to be barren. The third wife’s name was Naza. When she failed to conceive a child, Mullah Saban bought himself a baby boy from someone on the mountain. Saban was happy, and all three of Saban’s wives fussed over the baby, but the infant died within a few months.

At that time, and for years afterward, it was the duty of Kupusovici’s women to fetch water for their families at a spring next to Juz-bin’s mosque. The women would gossip and gabble as they waited to fill their water jugs. They would complain about their aches and pains. They would talk of how they had planted entire fields with seeds that did or did not sprout. They would commiserate with one another on how their drunken husbands beat them and kept them up all night. And they also cackled about Mullah Saban. They were sure he had been cursed with impotence because he had swindled somebody out of the gold ducats he had stashed in his house. It did not take long for the women to begin jabbering about Saban’s third wife, Naza, and how she had taken a shine to one of Mullah Saban’s sharecroppers, a son of Hujbo Celik named Salih. And it was not long thereafter that Mullah Saban caught Naza and Salih together.

“You will go with him,” Saban told Naza.

“No, I will not.”

“Bring me branches from an oak tree.”

Naza obeyed. It was the duty of a Muslim wife to obey. Always,

Mullah Saban put the oak branches into the fire in his hearth and blew on the flames. He watched the fire consume the branches and turn them into glowing orange coals. Naza waited. Saban took his walking stick. He pointed it at his wife as if he were going to beat her.

“You are going with him,” Mullah Saban said. “Dance oil the coals and tell me you are going with him.”

The woman pressed her bare foot onto the coals before she agreed to leave.

“Go,” he said. “Now.”

Naza left the house next to Juz-bin’s mosque and married Salih Celik. By him, she gave birth to a son named Hasan and at least five daughters, one of whom died in childhood of a snakebite. Mullah Saban lived for years in his house with the store on the ground floor, but he passed away without having fathered an heir. As he lay dying, he summoned to his bedside all of his wives, including Naza. He gave each one a third of his property. Salih and Naza Celik received a plot of land near the Cross. They were tenant sharecroppers no longer.

HASAN CELIK was born in 1909, according to the birth records anyway. He was a quiet child with olive skin, dark hair, and chestnut eyes. By the time he was born, the Austrians had already introduced some of the miracles of the Industrial Revolution to Visegrad and begun wrenching the people of Mount Zvijezda out of the Dark Ages. After July 4, 1906, the unpredictable gusts of wind blowing up the mountainside began to carry with them the faint whistle of a distant steam locomotive. The tiny train, called by the diminutive “Ciro,” or “Choo-Choo,” by everyone who spoke the Serbo-Croatian language, chugged its way from Sarajevo along a band of narrow-gauge tracks that ran through tight tunnels and along the sides of deep river gorges before rattling over the Drina on a new steel bridge and hissing and wheezing its way into Visegrad station. Passengers could now travel between Visegrad and Sarajevo in four hours instead of the two days it had required to make the journey on foot since Mehmed Pasha had built his bridge. The Austrians paid local men money to build the steep stone embankments, blast open the tunnels, and lay the tracks. A few of the Celik men went to work on the railroad after the line was completed, and other peasants found jobs as lumberjacks or woodcutters in local sawmills that could now ship the area’s abundant hardwood to distant markets.

Most families on Mount Zvijezda, however, remained on the periphery of the money-earning world and beyond the domain of steam power, watches, and books. They continued to till their fields with wooden plows drawn by oxen or horses. The Muslim landholders continued to collect their dues, though by now most of them had sunk into a poverty almost as miserable as that of the sharecroppers around them. Many men on the mountain lived for their addiction to their plum brandy. They awoke to it each morning and downed it before going to bed at night. Muslim men reveled in the brandy despite the prohibition on alcohol handed down by the Prophet Muhammad in the Koran, and the Serbs had no such religious prohibition. The peasants had found communion in the brandy for as long as anyone could remember, and this communion, for the time being at least, seemed rooted more deeply than a sense of nation or religion. Rare among them was the man who did not take God’s name in vain more often than he prayed to Allah or the Christ Jesus.

The mental calendar of the mountain might just as well have been anchored to the plum harvest and the brandy making in late fall and early spring. Not every one had a still, and, if later custom is any indication, the Celik menfolk in their baggy trousers, black wool cummerbunds, and maroon fezzes would distill the brandy at the Radovanovic place or with the Mitrasinovic men. There was nothing much else to be done at brandy-making time, nothing that could not be done drunk anyway, so the men would take turns for days on end feeding branches to the fire, tasting each new batch of brandy, and scooping out the bubbling mash with long-handled ladles when it was done. Sometimes they would sit up all night arguing and swearing on the pussies of each other’s mothers. They would roast potatoes on the fire, trade lies, tell tales, and play practical jokes. One of them might pull out a wooden flute and play a tune that began the kolo, the dance they all seemed to know without ever having learned it. The Muslim women in their billowy dimije and drooping veils would take the arms of their Serb sisters and dance about the yard, two steps forward, left foot behind right, right behind left, one step back, jump, and two steps forward.

* * *

THE men on Mount Zvijezda were preparing for the fall brandy making in 1908, when Austria touched off an international crisis by announcing that it had unilaterally annexed Bosnia. Serbia girded itself for war before Russia stepped in and calmed the situation by means of diplomacy because St. Petersburg was not prepared to go to war over Bosnia. Within a few months, however, Serbia’s army had begun creating networks of secret agents in Bosnia whose goal was to wrest the region from Austria’s control. Serbia grew even more bold after popular wars in 1912 and 1913, when the tiny country doubled its size by recapturing Kosovo and other territory from the Ottoman Empire. In May 1914, one of the Serbian army’s spy networks smuggled into Bosnia a pistol and a young Bosnian Serb student who could recite by heart epic poems about the medieval battle at Kosovo. On Vidovdan, June 28, this student, Gavrilo Princip, stood on a Sarajevo sidewalk and shot to death the heir apparent to Austria’s imperial throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, and his wife, Countess Sophie Chotek. Animosities toward Bosnia’s Serbs erupted into violence immediately after word spread that the Habsburg archduke and his wife had died. For days, Muslims and Croats looted Serbian Orthodox churches and Serb-owned shops, houses, and apartments in Sarajevo, Visegrad, and other towns.

Under pressure from Germany, Austria declared war on Serbia a month after the assassination. The rival alliances that had pitted Europe’s great powers against one another clicked into force, and World War I began. Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Turkey faced off in total war against France, Great Britain, and Serbia’s main backer, Russia. Salih Celik was drafted into the Austrian army and sent from Kupusovici to fight Bosnian Serb insurgents in the mountains just west of the Drina. The bulk of the Austrian forces crossed the river into Serbia, intending to punish quickly and once and for all. Against all odds, however, the Serbs kicked the Austrians back across the river and overran the western slopes of Mount Zvijezda. All of Visegrad was evacuated across Mehmed Pasha’s bridge before the Austrian army pulled out and blew up the stone bridge’s seventh arch. Naza packed up Hasan and the rest of her children and fled westward with several thousand other Muslims. The refugees traveled on foot and in oxcarts for days before reaching Bosnia’s western edge. When they arrived, Naza got word that Salih had been killed in a clash with a band of Serb guerrillas in the mountains above Srebrenica.

Bitter after its initial defeats, the Austrian army treated Bosnia’s Serb population as a fifth column. Vigilante gangs of Muslims and Croats carried out gruesome attacks on Bosnian Serb villages. Austrian police rounded up Serbian Orthodox priests, teachers, merchants, community leaders, and anyone else suspected of belonging to Serb nationalist organizations. Thousands of Serbs were driven into Serbia. Others were pitched into concentration camps or executed by hanging and firing squad. In the end, however, after battling heroically against invasions by Austria and Germany and after losing about a quarter of its population to fighting and disease, Serbia emerged on the victorious side.

The war destroyed or fatally wounded all of the old European empires. It also marked the emergence of a new world power, the United States of America, and the ascendancy of the idea of “self-determination of nations,” the right of the nations submerged within the old empires to form independent nation-states. The Austrian Empire was broken up into a patchwork of nationstates, including rump Austria, the country that became the heartland of Nazism. Orthodox Russia fell to the atheist Bolsheviks, and parts of the old Russian empire broke away. The Ottoman Empire shrank into the modern secular state of Turkey. Germany, the nation held to be most responsible for the war, was humbled and required to pay war reparations that created the economic chaos and bitterness that would eventually fuel the rise of Adolf Hitler, the unification of Austria and Germany, and the Germans’ second march against the Slavs of eastern Europe and Russia.

Bosnia descended into anarchy after the Austrian authorities withdrew. Serb sharecroppers rebelled against their Muslim landlords, and vigilantes indiscriminately killed Muslim peasants, often in retaliation for the killings of Serb civilians by Muslims and Croats in the service of Austria during the war. Serbs demanded Bosnia’s immediate unification with Serbia. Instead, however, a new state was forged from the lands inhabited by southeastern Europe’s Serbs, Croats, Muslims, and other Slavs. This new country was supposed to become the nation-state of the “South Slavs,” or “Yugoslavs,” and was initially called the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. It became the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1929, after years of political instability provoked its Serbian king, Aleksandar I Karadjordjevic, a direct descendant of Karadjordje, to declare a dictatorship and create a police state.

Most Serb leaders assumed Yugoslavia to be an extension of the old Serbia’s territory and a fitting reward for victory in a war that had cost the Serb nation dearly. Serbs took over the new country’s administration and bragged that they had “liberated” the Croats, Slovenes, and other Yugoslavs during the World War. Farmlands that had belonged to Bosnia’s Muslim beys, kapetani, and agas were expropriated without compensation and handed over to their former tenant sharecroppers. Police thugs and the army, whose generals were almost all Serbs, cracked down on nationalist organizations, and especially on Croats who wanted little to do with the new state. Bosnia’s mainstream Muslim Slav leaders opted to support the Serb king for fear that Bosnia would be swallowed up by Serbia and Croatia if Yugoslavia disintegrated. Despite this support, Serb extremists showed alarm at the large number of Muslims living within the new state’s borders and called for intermarriage to dilute the Muslim population and, if that failed, expulsion of the Muslims or their forcible conversion to Christianity.

NO international border ran along the crest of Mount Zvijezda after World War I. The Austrian customhouse and barracks in Odzak stood empty, and “the Customs Area” became an empty meadow. Naza Celik and the other Muslim refugees had returned to Visegrad to find that three of the arches of Mehmed Pasha’s bridge had been blown away. Their homes were still intact, but a cannon shell had carved a chunk of stone from the minaret beside Juz-bin’s mosque. The traditional agricultural cycle on the mountain began to turn as it always had before the war. The plows were still fashioned from wood. Grain was still harvested with hand scythes and milled at water wheels driven by the mountain streams. Muslim women still covered their faces in public. Herbal treatments, folk remedies, and citations from the Koran scribbled on paper and swallowed were still the only hope for people stricken with tuberculosis, typhus, syphilis, diphtheria, and other diseases.

Few peasants from Mount Zvijezda found jobs even after the government began investing capital in the Visegrad area. A couple of new sawmills opened. A new bomb factory and a chemical plant brought work to several thousand people. The old Austrian customhouse in Odzak became the headquarters for the local precinct, and in 1924 an elementary school opened in the building that had been the Austrian barracks below the Mitrasinovic family’s house. For the first time, teachers arrived to give reading lessons to the peasant children. Muslim parents refused to send their daughters to school, and many of their sons gave up reading altogether once they finished the fourth grade. The teachers also taught basic arithmetic and Serbian history. They led their pupils on nature excursions through the nearby forests and marched them up onto the crest of Mount Zvijezda. On the sides of Stolac, Zvijezda’s highest peak, the pupils sipped water from a spring reputed to be the coldest in all of Bosnia. Nearby, they dropped pebbles into the blackness of a vertical cave. They listened as the stones clicked against the rough sides of the shaft and echoed and echoed and echoed for as long as it took the class to sing a song. They called the cave Zvekara, “the Clicker.”

Hasan Celik was already too old for school by the time the first teachers arrived in Odzak, and he never learned to read. His widowed mother, Naza, remarried after the war and moved into a house a few yards away from the place she had shared with Salih on the Cross. Sometime during the late 1920s, Hasan married Ajka Kozic, a Muslim girl with green eyes and sunken cheeks who came to Kupusovici from a village a mile or so across the mountain. Hasan and Ajka’s family grew quickly. Their first child was a son, and, since Muslims are forbidden to name sons after their fathers, they called the boy Salih in memory of his grandfather. A daughter, Latifa, soon followed; then two more sons, Avdo and Esad. Hasan built his family a new house with a stone foundation, whitewashed wooden walls, and a pine-shingle roof. Through the windows, Ajka could gaze out over the Drina valley and hold up her children and show them Zvijezda’s stone walls and towers, its rolling terraces, and its patchwork of fields, pastures and forests. She could show them the handiwork of Jerina the Damned and her legion of soldier-slaves, and the children could feel the unpredictable gusts of wind, smell the aroma of the pine resin and the burning wood, and hear the rustling leaves, the tinkle of cowbells, and the singsong voices yodeling, “Yeoooo! Yeoooo! Coming hooome! Coming hooome!”

By mid-January 1941, Ajka was pregnant again. The baby was expected to arrive with the plums.

(C) 1998 Chuck Sudetic All rights reserved. ISBN: 0-393-04651-6

Article found at New York Times.

Image: The Emperor’s Mosque set ablaze by Bosnian Serb Army in Visegrad, June 1992.

Image: The Emperor’s Mosque set ablaze by Bosnian Serb Army in Visegrad, June 1992.